Mills Of The Ver Valley

When The Ver Was The Real Source Of Power In The Land

For centuries the Ver turned mill wheels which ground grain into food for people and livestock and which powered the cleansing and thickening of cloth, the sawing of wood and a host of other small industrial processes.

The main local landowner and source of political and economic power in the Middle Ages, St. Albans Abbey, knew how essential milling was to daily life. The punishments they imposed for private milling forced people to pay to use the Abbey’s watermills, helping to incite the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt locally.

Only a few of the Ver’s older mill buildings remain today, the remainder lost to fire, re-building, decay and demolition. Precise sites, names, uses and building dates are often uncertain. Mill buildings that survive are now used mainly as private dwellings, small businesses or restaurants.

Clean Power

It’s worth reflecting that over a distance of less than 10 miles of its 15 mile length, the Ver’s waters powered around a dozen mills, providing renewable energy with no cross-generational nuclear risk and negligible carbon footprint – clean power! This density of water-milling was not uncommon in Hertfordshire and beyond – the Colne, into which the Ver flows, served nearly thirty watermills.

Unreliable Flow

All this power may seem at odds with the trickle often seen in the Ver today, but remember the flow was greater prior to the substantial depletion of the chalk aquifers, which feed the Ver, to provide us with water. Also, we need to remember the ingenuity with which water was diverted into leats (mill stream channels) and mill ponds to provide powerful heads of water to drive mill wheels. Even so, the flow was not always reliable – in the 13th century the Abbot of St. Albans built a mill to be driven by horses because of the Ver’s capacity to dry up in summer.

The water supply was not predictable enough for milling to be sustained north of Redbourn. There are no known watermill sites before the Ver is joined by the Red River (the stream which gives Redbourn its name), behind the Chequers pub on Watling Street just south of the village. There was a silk mill in Redbourn village, but this was a 18th century steam-driven mill. The Domesday book refers to two mills in Redbourn, and whilst it is possible that there may have been mills within the present village, the two referred to are generally thought to refer to the known watermill sites south of the village: Do-Little and Redbournbury Mills.

Do-Little Mill

The photographs show the handsome mill house on Watling Street (today’s A5183) and its adjacent barn. These private residences mark the site of Do-Little Mill. Over the centuries it had been re-built and known variously as the Bettespool Mill, Malt Mill, Water Corn Mill, Redbourn Little Mill and finally Do-Little Mill. The mill race was powered by a large mill pond rather than a millstream, reflecting the unreliable flow of the water here. It was converted to paper milling in 1753, burnt down in 1783, rebuilt as a corn mill and closed in 1927.

Today’s buildings and the former millpond lie on the west side of Watling Street, but the mill was on the east side. It was the widening of Watling Street in 1950 which caused the mill to be demolished.

According to the mediaeval chronicler Thomas Walsingham, in 1344 a 5 year old girl’s recovery from falling into the mill race and being thrown out by the wheel was due to her mother’s prayer to St. Alban.

Redbournbury Mill

This beautifully located working mill is well worth a visit – normally open and working on Sunday afternoons. Bread and flour can be bought there some mornings. Why not buy your bread here if your morning commute takes you along the A5183 between Redbourn and St. Albans? See Redbournbury Mill.

Milling at Redbournbury goes back to at least Saxon times. Variously owned by the Abbey, the crown and Gorhambury Estates, it was much re-built in 1790 and restored after a fire in 1987 – seven centuries after the mediaeval mill here had also burned down!

Using sluice gates, a “leat” was built to divert water from the river and build up a head to pour over the mill wheel. The water filled buckets in the wheel, the weight keeping it turning. Water power was first supplemented by the end of 19th century by a steam or gas engine. The last tenant in the 1950s was Ivy Hawkins, “the last lady miller in England”, whose family had run the mill since the 19th century.

The mill was re-built after the 1987 fire. A 1930s diesel engine was obtained and restored to provide power to turn the stones to grind the local wheat into the flour to make today’s bread.

Shafford Mill

This handsome building dates mainly from the 1840s. It features a long, and still flowing, mill stream above the meadows to the east of Watling Street between St. Albans and Redbourn. The now private house and garden are on the ‘island’ between the millstream and the river channel.

In 1669, the miller here also farmed wheat and barley, ran a flour shop and leased Redbournbury mill! Shafford, Do-Little and Redbournbury mills were then owned by the Speaker of the Restoration Parliament, Gorhambury-based Sir Harbottle Grimston.

Pre (or Prae) Mill

Pre Mill, just north of the Pré Hotel, was most recently a saw mil, now derelict – the photograph is from the 1980s. But milling here also goes back to the Middle Ages. The name probably comes from the nearby Roman Praetorian Gate to Verulamium. The other photographs show the neighbouring mill cottages, and Pre Mill House from the Ver meadows looking east from the Gorhambury estate. In the 16th century, Prae Mill pumped water up to Gorhambury House.

There is some evidence of other mills between Shafford and Kingsbury – the site of a Ditchmill mentioned in the late 12th century is either where Prae Mill is now or a little downstream.

Kingsbury Mill

Another mill and accompanying miller’s house well worth a visit. The museum containing the mill workings – and the waffle house restaurant in the mill – are open most days.

This was the Abbot’s malt mill, in the parish of St. Michael’s, St. Albans, and passed into Sir Francis Bacon’s family at Gorhambury after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The present building is Tudor, with a later Georgian brick façade, but the site is probably one of the thee St. Albans mills mentioned in the Domesday book. Milling for flour and then animal foodstuffs continued until the mid 20th century. In 1973, the mill was turned into a working mill museum, waffle house and gift shop.

Abbey Mills

Opposite the Ye Olde Fighting Cocks inn in Verulam Park, these were last in use as silk mills, to which they had been fully converted in 1804. The Abbey Mills had been important corn mills when the Abbey was at the height of its power, and probably long before.

The mill race still gushes out opposite the inn, although the once-successful silk mills were closed in the 1930s and demolished in the 1950s. The mill buildings are now used as houses and apartments.

Cotton Mill

This photograph of the Ver flowing between the old swimming pool and the Cottonmill Lane allotments shows the site of an important St. Albans mill from the late 18th to late 19th century. Used variously for diamonds, cotton, candlewicks, wool and grain, in the 1840s over 60 people worked in this mill.

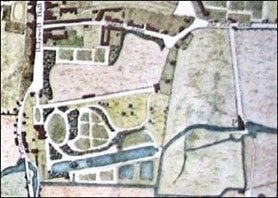

The map detail is from an 1822 map in Clutterbuck’s The History of the County of Hertford. The letter P shows the cotton mill where the river flows under Cottonmill Lane. Holywell House and its ornamental lake no longer exist.

The Stankfield Mill referred to the 12th century is generally thought to be have been located here, although Chris Saunders (see sources) locates this between Sopwell and New Barnes Mills.

Sopwell Mill

The mill on this site is predominantly late Victorian after fire destroyed its predecessor, a little further upstream, in 1868. It is now a private house, Sopwell Hill Farm, just off the Ver Valley Walk further down Cottonmill Lane.

Sopwell Mill was probably one of the three St. Albans mills referred to in the Domesday Book. There was certainly a mill here at the time of the Peasants’ Revolt. It was still grinding corn until the Second World War, and had been a paper mill in the 16th and 17th centuries.

New Barnes Mill

This mill at the bottom of Cottonmill Lane stands near to the Sopwell House Hotel. The present buildings, used for light industry and business, date mainly from the late 19th century, although have been extended as recently as the 1990s. Again, there was earlier milling here under the Abbey’s control. Flour was milled here up to the 2nd World War.

Park Mill

Park Street’s mill, near where the Ver crosses Watling Street for the last time, was another of the Abbey’s mills, believed to have been built in the late 11th century. The present building is a 19th century structure which has now been converted into flats.

The mill wheel is visible, although the millstream has been cut off.

There may have been another mill further south of Park Mill, but no evidence remains.

Moor Mill

Another of the Abbot’s mediaeval mills, this last mill on the Ver still has its water wheel visible inside what is now a public house and conference centre. A meal may cost you more than the £11 which it cost the Abbots of St. Albans to rebuild this mill in 1351. The present building dates from 1762 and was working until 1939.

Sources

A History of St. Albans by James Corbett. Phillimore, Chichester 1997 ISBN 1-86077-429-6

A Source Guide to the River Ver and its Valley by J.C.Green. The Ver Valley Society 1996

Made in St. Albans: Ten Town Trails Exploring St. Albans Industrial Past by Michael Fookes 1975 ISBN 0 9528861 0 3

St. Albans 1600-1700 edited by J.T.Smith & M.A.North. University of Hertfordshire Press 2003 ISBN 0 9542189 3 0

The Mills of Redbourn by Alan Featherstone. Reeve, Wymondham 1993

Watermills of the London Countryside Volume II by K.C.Reid. Charles Skilton Ltd, Haddington 1989 ISBN 0284 98806 5

3 Watermiils in St. Albans by M.Leamy & E. Parker. Published by the St. Albans Teachers Centre 1976

The website of the former Keeper of Field Archaeology at the Verulamium Museum, Chris Saunders

For this “Mills” section we are indebted to Charles Edwards a Ver Valley Society member who researched, wrote the notes and took the pictures – Many thanks Charles.